Virtual Reality in Context

This post was originally composed earlier this year as a white paper for Inhance Digital following the production of the agency’s first two Oculus-driven virtual reality experiences.

Every medium is a context for a message, with characteristics that shape any narrative it conveys. At the same time, every medium has its own contexts: historical, cultural, and technological. These two assertions could not be more relevant in the case of what we call virtual reality (VR) — and an understanding of the various aspects of these contexts is valuable when imagining and designing VR experiences.

VR in the history of technology and popular culture

Alternate realities have been a part of human culture for as long as there has been human culture, manifested as religious experience, dreams, meditative states and other altered states of consciousness. The idea is nothing new, to be sure, but in these historical examples the nature of the experience — the “content,” as reported by the conscious mind — comes from elsewhere: it’s attributed perhaps to divine intervention, or, later, as analytical psychology developed, the depths of the unconscious. Many possible sources are posited, but none would be considered intentional, rational products of the human mind.

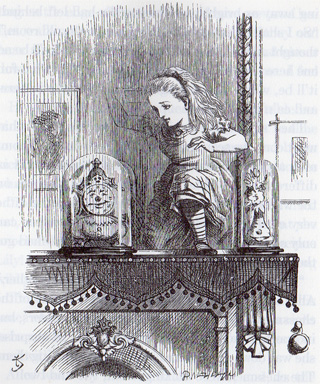

John Tenniel’s illustration from

Through The Looking-Glass by Lewis Carroll

Alice might pass through the looking glass, but few considered the idea that she might create a new looking-glass world of her own, where others could explore and learn.

It was in the 20th century that a new concept began to take hold in popular culture: the possibility that humans themselves could consciously and deliberately create and control immersive and complete alternate realities 1.

The seed for the concept of these sorts of artificial realities may have been planted around the end of the 19th century, with the advent of photography and cinema: devices which allowed one to create a startlingly (at the time) realistic representation of the real world. While these examples existed only within a frame or proscenium, the futurists of the era soon began to extrapolate and imagine where new technology could take us.

From the state of “half-life,” a form of cryonic suspension that maintains consciousness and the ability to communicate described by author Philip K. Dick in his novel Ubik (1969), to the idea of “the Matrix” — a “cyberspace” where people are “jacked in” their entire lives in the film of the same name (1999) – artificial realities have been an increasingly significant part of popular culture and contemporary mythology.

The term “cyberspace” was introduced in the 1980s by author William Gibson, first in his short story Burning Chrome (1982) and later in Neuromancer (1984): “Cyberspace. A consensual hallucination experienced daily … A graphic representation of data abstracted from the banks of every computer in the human system … Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind, clusters and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding.” In Gibson’s world, “jacking in” involved complete immersion in the artificial environment.

In cinema, these concepts were popularized by movies such as TRON (1982), Brainstorm (1983), The Lawnmower Man (1992), and Virtuosity (1995).

About the same time, actual VR technology — previously found primarily in esoteric military, academic and industrial applications 2 — began to become accessible to the general public. Jaron Lanier, one of the modern pioneers of the field (and who popularized the term “virtual reality”) founded the company VPL Research in 1985, releasing consumer-level VR products including a head-mounted display that could track the user’s movements.

In 1991 Sega announced the Sega VR headset with LCD screens in a visor and inertial sensors that allowed the system to track and react to the movements of the user’s head. The Virtual Boy was created by Nintendo and released in 1995.

But the former never reached beyond the prototype stage; the latter was a commercial failure. And by the end of the century popular culture seemed to lose interest in VR offerings as mainstream products. Indeed it became something of a joke: “the ‘death of VR’ had become a standard narrative.”3 Why? One reason might be that the technology just didn’t work very well: the sensors, processors, and display technology simply weren’t up to the task of creating a truly responsive, immersive environment.

But now all this is changing.

Today, advanced sensor technology, powerful CPUs and graphics processors combined with high resolution displays are catching up with the intentions of artists and experience designers, and are available at low cost on consumer-level equipment.

It’s worth pointing out that as of this writing, the technology still hasn’t quite fully arrived: the Oculus Rift DK2 is not yet a real, shipping product, and the Samsung Gear VR is still labeled an “Innovator Edition,” meaning that it is “intended specifically for developers and early adopters of technology” — but nonetheless the platforms are functional and ready to be exploited.

VR technology now joins photography, cinema, and interactive media as not just a way to create immersive environments and experiences, but an increasingly viable way to convey messages and tell stories.

What differentiates a “virtual reality” experience from one that is simply “immersive?”

The term “immersive” is defined as “pertaining to digital technology or images that deeply involve one’s senses and may create an altered mental state” — and there are many ways to create an experience that fits this description.

One method that has been used for years involves the use of multiple video projectors to fill a room with video, surrounding the audience, coupled with multi-channel audio. Inhance has created numerous “surround theaters” of this sort, including an installation for NASA that allowed a group of people to experience the illusion of standing on the surface of the moon.

All virtual reality (VR) platforms meet the basic criteria of being “immersive.” But a modern VR platform creates an individualized experience, using dedicated hardware that typically involves, at a minimum, the use of two specialized technologies:

- Stereoscopic displays

- Head-mounted movement tracking

Stereoscopic displays present independent video images to each eye of the viewer, generating the illusion of a three-dimensional world with depth.

A head-mounted display (HMD) with sensors such as accelerometer, gyrometer and magnetometer allow the software driving the system to track the position of the viewer’s head, and generate in real time an image of the virtual world that is consistent with the direction in which the viewer is looking. This must be accomplished at a very rapid rate in order to create a “believable” experience (and avoid discomfort).

Headphones for stereo music and sound effects are also a typical component of the system. Additional components that can increase the sense of full immersion may include proximity sensors, 3D audio, force feedback, and controllers such as sensor-equipped gloves and omnidirectional treadmills.

The result is an unprecedented level of realism and a range of new possibilities for interaction within a virtual world.

How does this change the way we tell stories?

The range of potential applications for fully immersive worlds — including environments that could never exist in reality — is vast. The technology opens myriad possibilities for communication that we are only beginning to exploit.

But it also subverts some long-standing assumptions and methodologies, and new paradigms for the medium have not yet been fully developed.

Traditional storytelling techniques have historically involved the assumption that the attention of the audience will be directed at a particular point, and there are many well-understood ways to manipulate or guide a subject’s attention. But in a VR world we’ve essentially handed over control to the viewer.

This means that many essential filmmaking techniques — approaches we use every day to create “traditional” visual narratives — won’t work in the VR world. Cinematic storytelling has long relied on precise control of the camera (e.g., manipulating depth of field, racking focus) and the art of continuity editing. Lighting for film usually depends on a given camera position and angle, among other parameters. We must now find ways to communicate the desired message while recognizing that many of these elements have become unpredictable.

As visual artists we also rely on design techniques that have been in use for hundreds if not thousands of years. Among these among these are the rules of composition that we learned our first year in art school: the rule of thirds, the golden mean, and so on. But in a 360-degree VR environment, it’s not possible to apply traditional rules of composition in the same way: without a “frame” around our experience, many of these old approaches no longer apply.

These are issues in any interactive environment, it could be argued, particularly in games driven by real time 3D engines, but usually in such cases there’s at least a frame, edges where the experience starts and ends — these are reference points that a VR platform is designed to eliminate.

Clearly, as the level of interactivity and immersion increases, so do the possibilities — but also the design challenges.

On a practical level, we must also consider the fact that while in a VR environment there are 360 degrees of visual information around the viewer, typically only 90-100 degrees of this is visible at one time, and the viewing angle cannot be predicted. This means the viewer will never see everything: the larger part of one’s hard work (and potentially one’s message) will simply be ignored (nonetheless, the full 360-degree environment must be modeled and rendered — a significantly greater amount of work and render cycles than in the case of a traditional 16×9 piece). Of course, allowing the audience to make multiple passes through the experience is often an option, and in some contexts this may also be desirable — but not always.

Finally, like any powerful technology, VR is not without the potential for potentially harmful misuse.

While not typically known for putting audiences in physical peril 4, interactive multimedia can involve various sorts of potentially harmful circumstances. In the case of a VR experience, the experience may indeed be “all in your head” — but as a fellow named Morpheus famously remarked, “the body cannot live without the mind” and, similarly, real physical discomfort (or worse) can result if we are not careful in what we are presenting.

The experiential “uncanny valley”

The term “uncanny valley” refers to a hypothesis in the field of aesthetics which holds that when anthropomorphic entities look and move almost — but not exactly — like natural beings, it causes a response of revulsion among some observers. For example, if a person sees an image of another (healthy) person, likewise an image of a simple doll, this is not likely to cause a negative response under normal circumstances. However the image of a realistic human likeness, say, an automaton — that is almost real but not quite natural — can be very disturbing.

While for different reasons, we noticed an analogous response to stimuli in a VR environment.

The response time and level of immersion is such that the mind “wants” to believe the experience is real. We noticed that dramatic violations of real world paradigms (e.g., laws of physics) that immediately dispel suspension of disbelief tend to generate less discomfort than subtle aspects of a virtual experience that the cognitive apparatus is trying to process but where something just isn’t quite right. For instance, in our testing we’ve found that when taking the viewer on a virtual “roller coaster ride” or fly-through, slow sweeping banked turns can actually be more disconcerting than dramatic swoops and dives.

“Simulator sickness” is a form of visually induced motion sickness, characterized by symptoms including disorientation (disrupted balance), oculomotor discomfort (e.g., eyestrain), and nausea. Sources of discomfort include the following: 5

- The sensory conflict that occurs when motion (acceleration) is conveyed visually but not to the vestibular organs

- Movement in the virtual world in ways that are not natural or predictable

- A limited or dynamic degree of control allowed to the viewer

- Extended intervals of time spent within the experience

And we must be aware (and make our audiences aware) of the lengthy list of health and safety guidelines associated with a VR experience, including the need to remain seated during the experience (as one may become disoriented or lose balance), the warning against use of the equipment by children under 13 (due to the potential adverse effects on visual and cognitive development) or people with a variety of medical conditions. And even for healthy users, a slight disorientation (like “sea legs”) can persist even after the experience is over, and audience members must be reminded that driving or use of heavy machinery should be avoided until all such symptoms disappear.

The application of VR experiences

Challenges notwithstanding, VR clearly offers immense opportunity to create experiences and tell stories in new and compelling ways. But is this really “the future?” Should every marketer — everyone with a story to tell — be running out and deploying VR systems in their exhibits, trade show booths, theaters and presentation centers?

As when one is considering any new medium or technology, the first step is to ask, “what is the story we’re trying to tell?” or “what is the transformation on the part of the audience we are trying to create?” — and then examine the opportunities provided by the technology in question and assess how they align with the goals. In the case of a VR platform, there are a number of obvious ways to further a range of narratives, including:

- The novelty and intensity factor: for the large number of people who have not used modern VR hardware, the depth of the experience is truly amazing, and the system is an example of new, cool tech.

- Making inaccessible environments accessible: real-world locations that are dangerous or otherwise restricted become available to general audiences of non-specialists.

- Creating environments that don’t (or can’t) exist in the real world: conceptual, dynamic and interactive environments can only explored in an artificial reality.

If the story to be told involves a theme of innovation, the VR medium can be the message, as in the Raytheon Oculus 360 Cyber Experience at the RSA trade show in San Francisco. This opportunity is likely, however, to be of limited duration, as the technology becomes increasingly mainstream.

The virtual world is well suited to stories involving places or environments where the audience could not otherwise go. This was the theme of the Shell Deepwater VR experience at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival (“go where no one else can go”) where the audience traveled to an offshore oil production platform, the sea floor, and all the way to outer space.

Similarly, futuristic or abstract environments can be visualized and explored, as in the Raytheon experience, where the “world of invisible data” was made visible in three dimensions. The nature of the 360-degree environment itself can also speak to narrative themes like ubiquity, unlimited possibility, and the idea of being surrounded by events or activity on all sides and is an excellent medium for any idea related to information overload or sensory overstimulation.

There are also some potential disadvantages of a VR experience to consider. The experience is usually available only to a limited audience: every member of the audience must have a dedicated set of hardware, and use of the hardware is not recommended for everyone (e.g., children under 13, those with certain medical conditions, etc.). And VR experiences are highly individual; audience members are literally cut off from the real world and each other. They may have robust interactions with the virtual environment, but no interactions with each other — so we don’t get the benefits of a shared experience, unless it is in the form of avatars in the virtual environment.

We’re still “physical.”

While one of the primary perceived advantages of a VR experience is the ability to place the audience in an immersive environment with the characteristics of three-dimensional space, research has brought into question the extent to which learning (involving spatial references, at least) is possible in a simulated environment that doesn’t involve actual, physical movement. From a famous experiment 6 involving cats “that were restricted such that they could not explore space through their own body movements … it was deduced that an ‘intelligent’ orientation in space, or any generally ‘intelligent’ behavior, develops from an active senso-motor exploration of the environment.” 7

Another consideration is whether the narrative in question is better served by a linear or an interactive experience.

The VR environment is, of course, inherently interactive, at the very least in that the viewer has control at all times of the angle of view: the system is constantly tracking the motion of the viewer’s head and generating an appropriate stereoscopic image consistent with the direction the viewer is looking. It’s worth noting, however, that this interaction is so subtle in modern VR systems that the viewer won’t even realize it’s happening — it just feels “real” (this is analogous to the example of continuity film editing, where you only notice it when it’s not working, otherwise the art and science is completely invisible).

A VR experience may be a sort of “roller coaster ride,” where the viewer is transported through a virtual environment as if on rails. In such a scenario, the viewer has limited control over motion, but still has complete freedom to look around in any direction. Even this limited level of interaction allows for myriad possibilities and many alternate narratives, as at any given moment the viewer will only be experiencing a fraction of the available visual information.

This type of scenario is suited to more traditional, linear stories, driven by a “cinematic” narrative with a beginning, development, and conclusion, predetermined timing and transitions, and a specific intended path through the virtual world.

The Raytheon and Shell experiences were of this type, where once the viewer had advanced past the initial “lobby” experience, they were essentially viewing playback of a 360-degree stereoscopic movie. This approach served these stories well, as in each there was a specific sequence of events and information we wanted the viewer to experience.

But it’s not the only possible approach. Alternatively, through the use of a real time engine the experience of the virtual world can be completely non-linear and interactive. Movement, direction, and manipulation of objects are under the control of the viewer. There is no predetermined timing or path. This approach is well suited to themes of freedom and exploration, or scenarios where the environment needs to be dynamic, responding to (or challenging) the viewer.

At Inhance we’re exploring all these options and more as part of our continuing process of exploiting the latest technological innovations to create new kinds of experiences – while maintaining a balanced perspective and considering all our options within the appropriate contextual frameworks. To think, for instance, in terms of “virtual” versus ”actual” is to subscribe to a false dialectic 8 since we all – as humans in the present era – live in a continuously dynamic, shifting space between and combining the two. And ultimately what we are developing are new tools for expression, that while extraordinarily powerful are only one more step in the long and multidimensional history of storytelling.

Endnotes

[1] The word “virtual” has an interesting (and somewhat sexist) history. The origin is the Latin virtus, meaning “potency” or “efficacy” – literally “manliness” – and is related to the root of “virile,” meaning, among other things, “capable of [pro]creation.” From this perspective, the salient aspect of “virtual reality” is not the fact that it is somehow artificial as opposed to actual – but rather that it is actively generated by man, creator of narratives, the storytelling animal.

[2] Personal simulation and telepresence environments have been around for a while. Immersive images have been used in the field of aerospace simulation for decades. In 1958, the Philco Corporation created one of the first telepresence visual systems using a CRT mounted on the operator’s head driven by a remote camera. “Sensorama,” an arcade game prototype developed by Morton Heilig in the mid-1960s provided a multisensory environment that included vibration and a chemical smell bank. In the late 1960s, a head-mounted display concept by Ivan Sutherland at MIT’s Draper Lab allowed computer-generated objects to be superimposed onto the real environment. An early example of an environment where viewers were able to control their own viewpoints or motion is the Aspen Movie Map, created by the MIT Architecture Machine Group in the late 1970s: using pre-recorded footage, an operator could “drive” through the town of Aspen, taking any route they chose. The Virtual Environment Workstation (VIEW) project developed at NASA Ames Research Center in the mid-1980s is another example of a helmet-mounted display technology with the addition of auditory, speech and gesture interaction within a virtual environment. “Tour of the Universe” (1985) in Toronto and “Star Tours” (1987) at Disneyland were among the first commercial entertainment applications of simulation technology and virtual display environments. The CAVE (CAVE Automatic Virtual Environment), a projection-based immersive visual and audio environment was created at the Electronic Visualization Lab and the University of Illinois in 1992.

It’s worth noting an interesting connection between the genesis of VR and music: As Benjamin Woolley has observed, Sutherland was inspired by the Link Trainer flight simulator. Edwin Link developed the first flight trainer in 1930, based on the pneumatic mechanism of player pianos.

Some sources for further reading:

- Scott Fisher’s article “Virtual Interface Environments”: Packer, Randall and Jordan, Ken, editors, Multimedia – From Wagner to Virtual Reality (W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1989).

- A Critical History of Computer Graphics and Animation, Section 17: Virtual Reality

- Benjamin Woolley, Virtual Worlds: A Journey in Hype and Hyperreality, (Blackwell, 1992)

[3] The history of VR through the words of important historical figures themselves is found in the highly entertaining article, Voices from a Virtual Past, compiled by Adi Robertson and Michael Zelenko.

[4] The word “typically” was chosen carefully, here. A recent project involving high power lasers mounted on robots dancing within inches of the faces in the audience comes to mind, but that’s another story.

[5] The source of most of this information, and an excellent reference in general, is the Best Practices Guide from the Oculus developer documentation.

[6] R. Held and A. Hein, “Movement-produced stimulation in the development of visually guided behavior,” in Journal of Comparative Physiology and Psychology 56, pp. 872-876.

[7] Rotzer, Florian, “Images Within Images, or, From the Image to the Virtual World” from the collection Iterations: The New Image, edited by Timothy Druckrey (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1993), 64.

[8] Zellner, Peter, Hybrid Space: New Forms in Digital Architecture (New York, NY: Rizzoli, 1999), 10.